When we think of the future of TV – or more specifically, the digital future of network TV – we tend to think around key concepts: over-the-top and direct-to-consumer distribution, à la carte availability, dynamic ad insertion, data-driven green-lights and so on. Yet, what’s always missing from this analysis is a more fundamental examination of what a digital network could actually be.

When we think of the future of TV – or more specifically, the digital future of network TV – we tend to think around key concepts: over-the-top and direct-to-consumer distribution, à la carte availability, dynamic ad insertion, data-driven green-lights and so on. Yet, what’s always missing from this analysis is a more fundamental examination of what a digital network could actually be.

One of the primary problems here is the starting point: TV Everywhere. TV Everywhere, to put it plainly, does not a digital network make. It’s about taking a linear product and putting it on the web – not rethinking the network construct itself. At its core, the traditional, linear TV business model is defined by its constraints. Each network has a finite number of programming slots (and even fewer primetime slots), which forces it to focus on maximizing “eyeballs” among a specific target demographic (or demographics) and programming thematically and/or tonally similar content. A digital network, however, faces none of these limitations. There’s no maximum – or minimum – amount of programming required, no limit to the number of genres and demographics it can serve, “no one size fits all” lead in show and no single performance metric. This fundamentally changes what a “TV” network can look like and be.

Netflix, for example, can be many things to many people. And it shows.

Netflix, for example, can be many things to many people. And it shows.

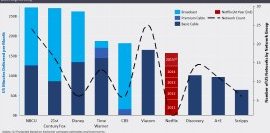

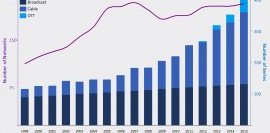

In the fourth quarter of 2014, Netflix delivered more minutes of video in the United States than the average broadcast network, twice as many as the industry’s largest cable network (The Disney Channel) and more than the bottom 118 (of roughly 225) cable networks combined. What’s more, this figure is up an estimated 40% (or 38 billion minutes) year over year.

Netflix is able to achieve this scale and rate of growth because in consumers’ minds, it is the Disney Channel. And AMC. And Syfy. And National Geographic. At first, Netflix’s streaming service was seen as a Pay TV competitor. Today, it’s most often viewed as premium cable network such as HBO (Netflix CEO Reed Hastings loves to make this very comparison). Yet it’s more accurate to describe the company as a multi-channel network group – a Time Warner or NBCU, not an HBO or USA.

Yet it’s more accurate to describe the company as a multi-channel network group – a Time Warner or NBCU, not an HBO or USA.

This isn’t an accidental demographic “creep”, either. Netflix is deliberately investing in niche content that, taken together, creates a mass market service. While it’s easy to get the impression that Netflix’s originals are widely consumed (perhaps even at the level of popular broadcast series), this actually isn’t the case. “As a general rule, the audience who watches House of Cards does not watch Hemlock Grove — and yet again, is not the audience that watches Arrested Development…There’s some overlap but surprisingly little, ” Netflix’s Head of Original Content Cindy Holland told Vanity Fair earlier this year, “I don’t think any genres are off-limits to [Netflix’s original programming]. We have a large subscriber base that consumes a wide variety of content.”

This approach flies in the face of the existing network playbook. Conventional wisdom says that specialized brands are better at building audiences, programming, marketing and ad sales (not to mention brand-wide carriage negotiations). Yet at the same time, it’s not clear that consumers value any of these supposed advantages. If a network could satisfy multiple genres, might that be preferred?